You can also find all 50 answers here 👉 Devinterview.io - String Data Structure

A string represents a sequence of characters and is fundamental for storing textual information in programming languages like Python, Java, and C++.

-

Character Encoding: Strings use encodings like ASCII, UTF-8, or UTF-16, setting rules for character representation.

-

Mutability: A string's content can be either mutable (modifiable) or immutable (unchangeable). The mutability often varies across languages.

- Concatenation: Joining two or more strings.

- Access: Retrieving characters using an index.

- Length: Measuring the number of characters.

- Substrings: Extracting portions of the string.

Strings in Python are sequences of Unicode characters and are immutable. Python offers a rich set of methods for string manipulation.

s = "Hello, World!"

print(s[0]) # Output: "H"Strings in Java are immutable sequences of characters. For efficiency, Java often stores its strings in a "string constant pool."

String s = "Hello, World!";

System.out.println(s.charAt(0)); // Output: "H"In C, strings are represented using null-terminated character arrays. C++ provides both C-style strings and a more advanced std::string class.

#include <string>

std::string s = "Hello, World!";

std::cout << s[0]; // Output: "H"Strings and Character Arrays have many similarities but also key differences in their usage and behavior.

- Strings: Dynamically allocated in many languages.

- Character Arrays: Explicitly allocated, typically on the stack.

- Strings: Immutable in many languages; once created, their content cannot be modified.

- Character Arrays: Mutable; allows for modification of individual elements.

- Strings: Provide built-in string manipulation methods, like

concatenate. - Character Arrays: Lack such convenience; require manual character handling.

- Strings: Might be less efficient due to potential dynamic resizing and metadata overhead.

- Character Arrays: More compact and efficient because of the absence of dynamic resizing overhead.

- Strings: Termination is managed internally in many languages and doesn't always rely on explicit terminators.

- Character Arrays: In languages like C, they require a null character (

'\0') to indicate termination.

- Strings: Preferred for text processing and higher-level abstractions.

- Character Arrays: Suited for low-level manipulations, like specific I/O operations.

A null-terminated string is characterized by its ending '\0' ASCII character (or 0-byte). This method was essential for memory management before dynamic memory allocation became common. Today, it's mainly used for compatibility.

In C, character arrays act as null-terminated strings. Functions like printf and strlen depend on the null character to determine string termination. While this approach is memory-efficient, it can be prone to overflow and length errors if the null terminator isn't verified.

- Performance: Null-terminated strings might slow down some operations.

- Safety: Always ensure strings are NULL-terminated to prevent memory issues.

- Compatibility: Use them when needed for specific systems or libraries.

Modern languages like Python and C++ offer advanced string types, such as Python's str and C++'s std::string, which are more convenient and manage memory better, reducing the need for null-terminated strings.

In the context of strings, mutability refers to the ability to change or modify an existing string object, whereas immutability implies that a string, once created, cannot be altered.

Many programming languages have predefined ways in which strings are treated. For instance, in Python and Java, strings are primarily immutable, but these languages provide mutable alternatives for specific use-cases.

-

Behavior: Any operation that seems to modify the string actually creates a new string with the changes and returns it, leaving the original string unaltered.

-

Example: In Python, strings are immutable. For instance:

text = "Hello" lowercase_text = text.lower() # Returns a new string in lower-case without altering 'text'.

-

Advantages:

- Thread-Safety: Immutable strings are inherently thread-safe, making them easier to use in concurrent environments.

-

Disadvantages:

- Memory Overhead: Generating a new string for every modification can lead to a higher memory footprint, especially with large strings.

- Efficiency Concerns: Creating a new string object can be more resource-intensive than modifying an existing one in-place.

-

Behavior: Mutable strings allow direct changes to their content without creating a new string.

-

Example: In Java, while the

Stringclass is immutable, theStringBuilderandStringBufferclasses provide mutable string implementations. Similarly, in C++,std::stringobjects are mutable and can be modified directly using functions likestring.replace()or by accessing individual characters. -

Advantages:

- Memory Efficiency: In-place modifications can save on memory by avoiding the creation of new string objects.

- Performance: Direct access and modification of string characters can be faster than creating new strings.

-

Disadvantages:

- Thread-Safety: Mutable strings can pose synchronization challenges in parallel or multi-threaded applications, necessitating extra precautions for proper management.

Let's look at the key ways in which different programming languages handle strings, ranging from mutable vs. immutable semantics to character encoding and more.

These languages serve as the roots of many modern programming paradigms:

- Character Encodings: Initially designed for punch cards, its support was later extended to more modern encodings.

- Data Structure: Strings are represented as arrays of characters terminated by a null character (

'\0'), which makes them mutable. - Character Encoding: Initially relied on ASCII, later supporting other encodings based on environment.

- Substrings: Provides substrings using the

Ada.Strings.Fixedpackage.

These widely-taught languages have left an indelible mark on programming education:

- Data Structures: Uses arrays or sequence data types to store strings.

- Character Case: Unlike many modern languages, Pascal retains a distinct difference between upper and lower case characters.

- Standard Library: Introduced the

std::stringclass, which offers a more comprehensive and safer string manipulation compared to C-style strings.

- Character Encodings: Strings are encoded in UTF-8 by default.

- Immutable Strings: Once defined, strings are immutable and cannot be changed.

These languages have seen widespread adoption in web and app development:

- Data Type: Strings are treated as a separate atomic data type.

- High-Level Methods: The String object provides numerous utility methods for string manipulation.

- Data Type: Strings are represented as immutable arrays of Unicode code points.

- Encoding Support: Python has excellent support for different character encodings, including built-in mechanisms to understand and manipulate non-ASCII strings.

- Character Encodings: String literals in source code are considered UTF-8 by default.

- String Mutability: Offers both mutable and immutable strings. The use of

.freezemakes a string immutable.

- Character Encoding: Traditionally, PHP strings used the ASCII encoding. With the shift to PHP7, strings are now assumed to be encoded in UTF-8 by default.

- Bi-Directional Support: Efficiently handles both left-to-right and right-to-left scripts, essential for rendering text correctly in languages like Arabic or Hebrew.

- Vectorized Strings: Text data are represented in vectors, enabling high-capacity storage and quick computations on strings.

While Strings are versatile, they are not the ideal storage for passwords or critical data due to their immutability and the associated risks of data remanence.

For sensitive data, a character array is often more secure, as it allows for explicit clearing and reduces chances of unintended exposure.

-

Data Security:

chararrays can be overwritten in memory, effectively erasing sensitive information. Conversely,Stringspersist in memory until garbage collection, posing a risk. -

Memory Protection: Since

Stringsare immutable, once created, their contents remain accessible in memory. -

Log Files and Dumps: Unintended logging or memory dumps could expose

Strings. Overwritingchararrays after use minimizes this risk. -

Thread Safety: In concurrent environments,

chararrays provide a level of control and safety thatStringsmay not.

Here is the Java code:

char[] password = {'p', 'a', 's', 's', 'w', 'o', 'r', 'd'};

// Clearing the password from memory

for(int i = 0; i < password.length; i++) {

password[i] = 0;

}String indexing is the system of assigning a unique numerical label to each character in a string, essentially placing them in an ordered list or "sequence".

In Python, strings support positive (forward) indexing where the first element is at 0, and negative (backward) indexing, where -1 points to the last element. The choice of indexing greatly influences the efficiency of different string operations.

Visualizing these two indexing modes brings clarity to their functional differences:

| Input String | Character Positions (Forward) | Character Positions (Backward) |

|---|---|---|

| "hello!" | ['h', 'e', 'l', 'l', 'o', '!'] | ['h', 'e', 'l', 'l', 'o', '!'] |

| "h e l l o ! " | [0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5] | [-6, -5, -4, -3, -2, -1] |

-

Access Single Character: Both forward and backward indexing can do this in

$O(1)$ time. -

Substring Operations:

- Backward:

-

Forward: In a forward-indexed string, getting substrings requires linear time complexity, leading to

$O(k)$ complexity.

-

Length Calculation: Both methods yield a time complexity of

$O(1)$ .

Here is the Python code:

# Efficiency of Forward- and Backward-Indexed Strings

# Single character access

forward_character = s[0] # O(1)

backward_character = s[-1] # O(1)

# Substring operations

forward_substring = s[:3] # O(k)

backward_substring = s[3:] # O(k)

# Length calculation

length = len(s) # O(1)Pascal Strings have been historically employed in the Pascal programming language.

Their unique feature is that they explicitly store the string's length, which provides both safety and efficiency advantages over null-terminated strings, commonly used in languages like C.

- Length Prefix: Pascal Strings begin with a distinct length indicator. This length is typically stored in one byte, allowing for strings of lengths from 0 to 255.

- Absence of Null-Terminator: Given the length prefix, there's no need for a trailing null-terminator as seen in C strings.

-

$O(1)$ Length Access: Thanks to the length stored at the beginning, retrieving the length of a Pascal String is a constant-time operation.

-

Safety: Pascal Strings reduce certain risks associated with string handling, like buffer overflows, which can arise with null-terminated strings. However, if the length prefix is tampered with or not correctly validated, it can lead to vulnerabilities.

-

Memory Efficiency: They can be slightly less memory efficient because of the additional length byte. However, in cases with many short strings, the absence of a null-terminator can make Pascal Strings more memory-efficient.

-

Binary Data Limitations: Pascal Strings can be used for binary data, but care must be taken. The length byte itself could be misinterpreted as content. Moreover, using only one byte for length limits the string to 255 characters.

Here is the C++ code:

#include <iostream>

int getPascalStringLength(const char * pascalString) {

unsigned char length = static_cast<unsigned char>(*pascalString);

return static_cast<int>(length);

}

int main() {

const char * pascalString = "\x05" "Hello";

int length = getPascalStringLength(pascalString);

std::cout << "Length: " << length << std::endl;

return 0;

}String concatenation involves merging two or more strings to create a single string. This process can be memory-intensive, especially for multiple concatenation operations with longer strings.

-

Simple Concatenation: In many languages, this method is intuitive but can be inefficient due to the inherent need for memory allocation and data copying.

result = str1 + str2 # Example in Python

-

Using String Builders or Buffers: This technique is more efficient as it avoids unnecessary memory allocations and data copying.

-

Double-Ended Queue (Deque): This method, often called "rope" in the context of very long strings, is efficient for large strings but can be slower for small ones. It breaks down the larger strings into smaller, more manageable pieces, \textbf{optimizing memory usage and improving performance for common string operations like slicing and concatenation}.

In Python, libraries like

collections.dequeenable this approach.

-

Simple Concatenation:

- Time Complexity:

$O(m+n)$ , where$m$ and$n$ are the lengths of the two strings being concatenated. This approach has a straightforward time complexity, directly related to the lengths of the strings being combined. - Space Complexity:

$O(m+n)$ if a new string is created.

- Time Complexity:

-

Using String Builders or Buffers:

- Time Complexity:

$O(m+n)$ , same as simple concatenation. - Space Complexity: Potentially

$O(m+n)$ , but it can be optimally$O(min(m,n)))$ if the builder or buffer is initialized at that size and then resized if needed.

- Time Complexity:

-

Double-Ended Queue (Deque):

- Time Complexity: Still

$O(m+n)$ , as all characters need to be processed in both strings. - Space Complexity: Typically

$O(m+n)$ , as all characters are stored, but it can be$O(1)$ in some implementations if the original strings can be modified in place.

- Time Complexity: Still

Substring search, commonly known as pattern matching, plays a crucial role in text processing tasks. Its efficiency is often analyzed in terms of time complexity.

The Big-O notation for substring search is often

However, different algorithms offer improved time complexities under specific conditions.

- Gale-Shapley algorithm

$O(n + m)$ : This is a two-pass linear-time algorithm. Its effectiveness is based on a large alphabet size, and it's especially useful on DNA sequences and similar datasets. - Knuth-Morris-Pratt algorithm

$O(n + m)$ : This linear time algorithm is particularly efficient for repetitive patterns thanks to its ability to avoid redundant comparisons. - Boyer-Moore algorithm: It includes tools like the "Bad Character Rule" and the "Good Suffix Rule" to obtain an

$O(n + m)$ average case. However, it can reach up to$O(n \cdot m)$ with certain patterns.

Here is the Python code:

def kmp_search(text, pattern):

lps = compute_lps(pattern)

n, m = len(text), len(pattern)

i, j = 0, 0

while i < n:

if text[i] == pattern[j]:

i, j = i + 1, j + 1

if j == m:

print("Pattern found at index:", i - j)

j = lps[j - 1]

else:

if j:

j = lps[j - 1]

else:

i += 1

def compute_lps(pattern):

m = len(pattern)

lps = [0] * m

length, i = 0, 1

while i < m:

if pattern[i] == pattern[length]:

length += 1

lps[i] = length

i += 1

else:

if length:

length = lps[length - 1]

else:

lps[i] = 0

i += 1

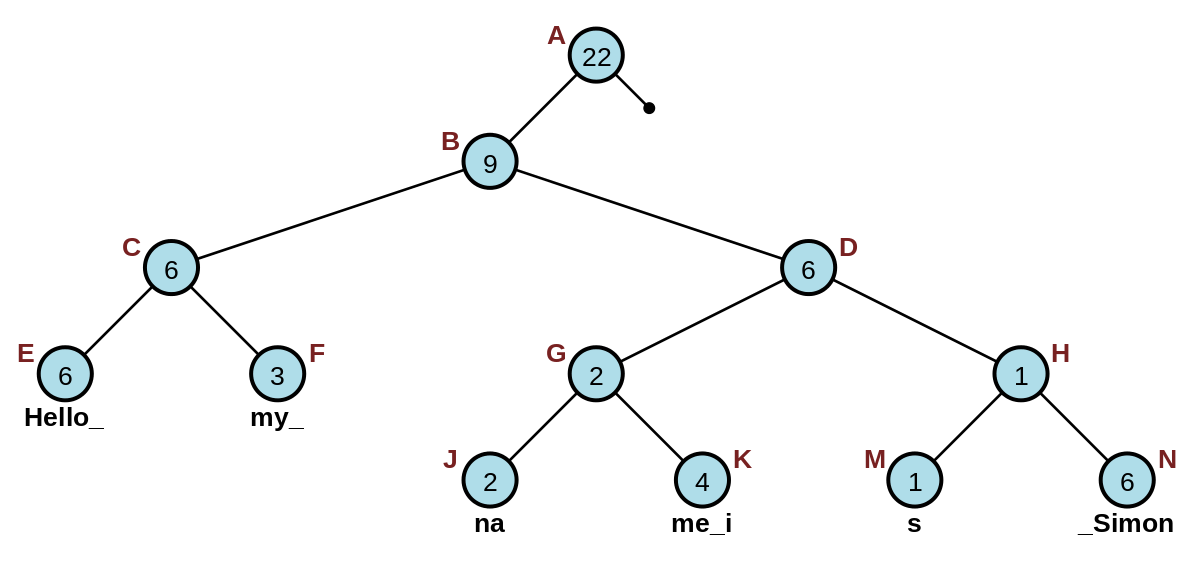

return lpsRope, also known as String-Tree, is a binary tree structure optimized for efficient string manipulation operations such as concatenation, insertion, and deletion.

Compared to standard strings (often implemented as arrays) which typically require

- Structure: Ropes are binary trees. Nodes have either two children or are leaf nodes containing strings.

- Leaf Types: Individual characters or substrings.

- Efficiency: Designed to minimize memory allocations and optimize string operations' time complexity.

- Efficient Concatenation: Ropes are optimized for quick string concatenation.

- In-Place Modifications: They support in-place updates without requiring the entire string to be copied.

- Performance on Large Strings: Ropes are particularly useful for operations on large strings as they avoid full traversals for certain operations.

- String Indexing: Random character access is slower than with contiguous memory structures.

- Memory Overhead: They can consume more memory compared to standard string arrays due to the tree nodes.

- Complexity: Their design and usage can be more complex than simple arrays.

Here is the Python code:

class RopeNode:

def __init__(self, text=None, left=None, right=None):

self.text = text

self.left = left

self.right = right

self.length = len(text) if text else left.length + right.length

def is_leaf(self):

return self.text is not None

def CharAt(node, index):

if node.is_leaf():

return node.text[index]

if index < node.left.length:

return CharAt(node.left, index)

return CharAt(node.right, index - node.left.length)

def Concatenate(left, right):

return RopeNode(left=left, right=right)

def Split(node, index):

if node.is_leaf():

return RopeNode(text=node.text[:index]), RopeNode(text=node.text[index:])

if index <= node.left.length:

left1, left2 = Split(node.left, index)

return left1, Concatenate(left2, node.right)

right1, right2 = Split(node.right, index - node.left.length)

return Concatenate(node.left, right1), right2

# Example Usage:

node1 = RopeNode(text="Hello,")

node2 = RopeNode(text=" World!")

root = Concatenate(node1, node2)

print(CharAt(root, 7)) # should print "W"The Rope data structure excels in certain scenarios but is not without its constraints.

-

Efficient Concatenation: Concatenating two ropes typically involves creating a new node pointing to the original ropes, rather than copying entire strings.

-

Lazy Evaluation: Ropes execute operations only when necessary, deferring specific computations. For instance, during concatenation, the actual underlying substrings remain unchanged until accessed, optimizing specific tasks' performance.

-

Memory Efficiency: Instead of storing the whole string contiguously, ropes use nodes holding parts of the string, making them suitable for representing larger strings without needing contiguous memory spaces.

-

Incremental Length Calculation: Ropes maintain the length of each node, alleviating the need for full traversal during operations like indexing or substring creation.

-

Balance and Performance Guarantees: Even in worst-case scenarios, operations such as indexing or concatenation in Ropes are bounded by

$O(\log n)$ time complexity, ensuring predictable and enhanced performance compared to traditional strings. -

Thread Safety: Many Rope implementations are designed to prevent concurrent access conflicts, making them ideal for multi-threaded environments.

-

Applications in Text Editors: Due to their efficient handling of operations like insertion, deletion, and slicing, Ropes are well-suited for text editors, especially for features like undo and redo.

-

Operational Complexity: Although Ropes can offer constant-time

$O(1)$ operations like concatenation and substr, ensuring these benefits demands intricate internal management and computation. -

Memory Footprint: While efficient for larger strings, Ropes might be less memory-efficient when representing very small strings or when the structure becomes highly fragmented. This inefficiency arises from metadata storage, such as node weights and balance factors.

-

Cache Performance: While traditional strings benefit from cache coherence due to contiguous memory, Ropes introduce additional pointer dereferences, possibly leading to increased cache misses.

-

Traversal Overhead: Elementary operations, such as character retrieval, entail tree traversals, making them more computationally intensive compared to their counterparts in regular strings.

-

Limited Mutability: Ropes are predominantly immutable, and while they can undergo specific transformations using intricate algorithms, straightforward mutations, like character replacements, are not intrinsically supported.

-

Algorithmic Overheads: Even though Ropes present impressive time complexities for several operations, they may have considerable constant factors. This characteristic can render them less efficient for smaller strings. For instance, a Rope's concatenation might be less efficient than a straightforward

appendon a regular string of moderate size. -

Integration with Legacy Systems: Ropes might not integrate seamlessly with older software ecosystems that predominantly utilize conventional string structures, potentially causing compatibility challenges.

Developed in 1995 by Hans-J. Boehm and Russ Atkinson, the rope data structure was designed to address the inefficiencies associated with conventional strings, especially regarding memory management, mutability, and performance in editing operations.

-

Buffered Input/Output: Ropes can process I/O operations with greater efficiency by minimizing the number of system calls.

-

Split At Arbitrary Positions: Ropes facilitate quick and efficient splitting, which proves beneficial for tasks like indexing, compressing, or partially loading files.

-

Text Editing: Ropes excel in managing editing operations for large text documents, making them ideal for applications like word processors and code editors.

-

Multimedia Compression: While ropes can be employed in multimedia applications, the specific advantage they offer in this context should be elaborated upon.

-

Data Digests (Hashing): Ropes can be advantageous when computing the hash of massive datasets without fully loading them into memory.

-

Unreadable Content: When memory-mapped, ropes can ensure that the data isn't easily readable from the binary executable. This characteristic can be useful in obfuscating or encrypting sensitive content.

-

Database Systems: Ropes can efficiently handle large text fields in databases, making them apt for managing content such as extensive comments sections or notes.

-

Distributed Systems: Owing to their segmented structure, ropes are conducive for distributing and processing documents across networked environments.

Prominent rope implementations can be found in libraries like Apache's stdcxx and Google's Sawzall. Python has its rope library, while text editors such as Emacs and some versions of Visual Studio employ the rope data structure internally to enhance text editing capabilities.

Ropes and StringBuilders are tools optimized for specific string manipulation scenarios. They each have unique strengths and weaknesses, making them suited for distinct use cases.

-

Rope:

- Strengths: Excels in read-heavy, append-heavy tasks, and multi-threaded environments.

- Weaknesses: Less suited for continuous, in-place modifications.

-

StringBuilder:

- Strengths: Designed for in-place modifications such as appends and insertions.

- Weaknesses: Not optimized for operations like substring extraction.

-

Rope:

- Substring: Efficient, especially with large strings.

- Modification: Less efficient for continuous in-place modifications.

- Complexities:

$O(\log n)$ for indexing,$O(k)$ for concatenation,$O(k + \log n)$ for splitting,$O(n)$ for substrings.

-

StringBuilder:

- Substring: Not optimized.

- Modification: Ideal for continuous in-place modifications.

- Complexities: Amortized

$O(1)$ for append.

- Rope: Best for complex string operations, concurrent editing, and read-heavy scenarios.

- StringBuilder: Primarily for continuous appending and modification, especially when memory optimization isn't important.

Here is the Python code:

# Rope example using the 'rope' library

from rope import Rope

r = Rope('Hello, World!')

print(r.slice(0, 5)) # Output: Hello

# StringBuilder example using Python's equivalent, 'io.StringIO'

import io

s = io.StringIO()

s.write('Hello, ')

s.write('World!')

print(s.getvalue()) # Output: Hello, World!Let's compare strings and ropes from the performance perspective.

-

Rope: Locating a character is

$O(\log n)$ due to tree traversal. -

String: Accessing a character by its index is

$O(1)$ .

-

Rope: Modifications, especially at arbitrary positions, typically incur

$O(\log n)$ complexity, but may also need potential rebalancing or node creation. -

String: Modifications, like insertions or deletions, especially not at the end, usually take

$O(n)$ since characters might need to be shifted or reallocated.

-

Rope: Concatenating two ropes often only requires the creation of a new node, which is

$O(1)$ . However, rebalancing might require additional time, leading to$O(\log n)$ in some cases. -

String: Appending a character or a short string is

$O(1)$ amortized, but can become$O(n)$ if reallocation is needed.

-

Cache friendliness: Contrary to the provided information, traditional strings are typically more cache-friendly due to their contiguous memory layout. Ropes, because of their tree structure and pointers, might result in more cache misses during traversal.

-

Memory Efficiency: While ropes can be more memory-efficient for operations that would otherwise require copying or reallocation in strings, they introduce overhead due to the storage of tree nodes. This overhead is especially significant for smaller datasets.

-

Strings: Best for smaller datasets where frequent, direct access to characters is needed and where modifications are less frequent or mostly happen at the end.

-

Ropes: Ideal for larger datasets or applications (like text editors) where operations such as append, insert, or delete at arbitrary positions are frequent.

Explore all 50 answers here 👉 Devinterview.io - String Data Structure