Unix (/ˈjuː.nɪks/; trademarked as UNIX) is a family of multitasking, multiuser computer operating systems that derive from the original AT&T Unix, developed starting in the 1970s at the Bell Labs research center - https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Unix

Many Unix-like operating systems have arisen over the years, of which Linux is the most popular, having displaced SUS-certified Unix on many server platforms since its inception in the early 1990s. - https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Unix

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Unix

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Unix_philosophy

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_Unix

- http://www.howtogeek.com/182649/htg-explains-what-is-unix/

-

Files and Processes

- Everything in UNIX is either a file or a process

ps auxto see the processes that are running, same as opening the "activity monitor"- http://www.ee.surrey.ac.uk/Teaching/Unix/unixintro.html

-

Exploring the root directory (in case you're ever wondering what all those files in

/are)

Setting Environment Variables

export MY_VAR=1

Reading Environment Variables

echo $MY_VAR

Note how the environment variable is no longer defined once you exit out of the shell and reopen it. The ~/.bash_profile file is run every time you open a shell. You can store variables that you would like to persist in there.

Check out all of your environment variables: printenv

- some basic ones http://www.ee.surrey.ac.uk/Teaching/Unix/unix8.html

$PATH is an environment variable that specifies where the executable programs are located.

which echofor example, will tell you where the echo command is located, it will be within one of the folders specified in$PATHotherwise you would have to call it explicitly every time as/bin/echo

Lets modify an environment variable in side your your ~/.bash_profile (macOS) or ~/.bashrc (Ubuntu).

-

First

touch ~/.bash_profile(macOS) ortouch ~/.bashrc(Ubuntu) in the terminal. This will create an empty file in your home folder if one doesn't already exist. If the file does exist, the touch command won't modify it's contents. -

Then open your

~/.bash_profile(macOS) or~/.bashrc(Ubuntu) file and place the following snippet at the bottom. This exports the environment variable PS1 which controls how your terminal display looks. All of the code inside this file is run every time you open a terminal.# set EDITOR as sublime text export EDITOR="subl --wait" # Define a function that returns your current git branch parse_git_branch() { git branch 2> /dev/null | sed -e '/^[^*]/d' -e 's/* \(.*\)/ (\1)/' } # Display present working directory and git path in bash prompt with colors export PS1="\u \[\033[32m\]\w\[\033[33m\]\$(parse_git_branch)\[\033[00m\] $ "

-

Close and reopen the terminal to see the change. Modifying the PS1 environment variable as you just did creates this nice prompt that tells you where you are as you move around directories:

-

Modify PS1 within the existing shell (instead of in the bashrc/bash_profile). Notice that since we didn't add this to the bashrc/bash_profile it doesn't persist when we open a new tab.

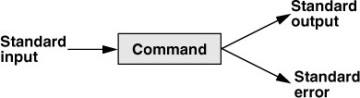

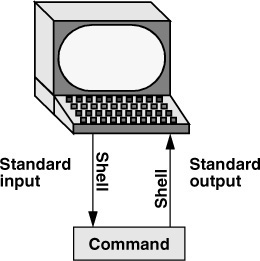

Originally I/O happened via a physically connected system console (input via keyboard, output via monitor), but standard streams abstract this. When a command is executed via an interactive shell, the streams are typically connected to the text terminal on which the shell is running, but can be changed with redirection, e.g. via a pipeline. - https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Standard_streams

source: http://www.informit.com/articles/article.aspx?p=2273593&seqNum=5

Figure 5-3 By default, standard input comes from the keyboard, and standard output goes to the screen

source: http://www.informit.com/articles/article.aspx?p=2273593&seqNum=5

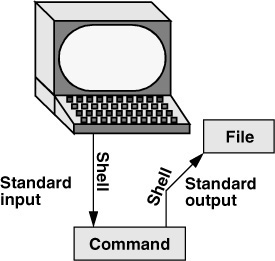

Figure 5-4 Redirecting standard output

command [arguments] > filename

source: http://www.informit.com/articles/article.aspx?p=2273593&seqNum=5

source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pipeline_(Unix)

Commands return exit codes when they finish running, 0is success, 1 is fail

Get exit code of the command you just ran with the following

echo $?

Error Codes other than 1 and 0 are more rare, but here are some examples: http://www.tldp.org/LDP/abs/html/exitcodes.html

Additional resource on exit codes:

http://bencane.com/2014/09/02/understanding-exit-codes-and-how-to-use-them-in-bash-scripts/

ls -l

source: http://linuxcommand.org/lts0070.php

- Look at permissions inside

~/Development/universe/solar_system/planets - Look at permissions inside

/Applications- notice how those are executable while the planets files are not.

chmod stands for "change mode", it is the command that lets you set permissions for a file

- http://computerplumber.com/2009/01/using-the-chmod-command-effectively/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chmod

- https://www.cise.ufl.edu/~shray/

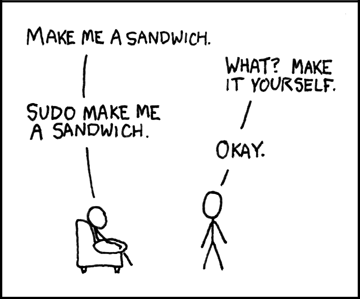

Prepend any command with sudo in order to run the command as root user. Try to avoid this unless you know what you're doing. But also know that it is often the solution if you get an error telling you that you don't have the permissions to run something.

http://unix.stackexchange.com/questions/3063/how-do-i-run-a-command-as-the-system-administrator-root

-

Make a file called

sayhello.pyin yourassignmentsfolder within~/Development.cd ~/Development/assignments touch sayhello.py

-

Open

sayhello.pyand type the following python program:#!/usr/bin/env python2 import sys name = sys.stdin.read() print "Hello " + name + "!"

-

Make sayhello.py executable.

chmod +x sayhello.py -

Run this program.

echo -n "John" | ./sayhello.py

This program below will add 1 to the input on STDIN.

#!/usr/bin/env python2

import sys

input_number = sys.stdin.read()

print int(input_number) + 1Save this program as a file called add1.py, chmod it, and execute it.